All The Dead Boys

A Conversation with Carter Smith

Best known for his 2008’s biological-horror freakout The Ruins, director Carter Smith has more recently made waves in the indie scene for a handful of off-kilter queer efforts including Jamie Marks Is Dead (2014), Swallowed (2022), and The Passenger (2023). A celebrated fashion photographer whose work has appeared in Vogue, GQ, W Magazine, and Men’s Health (among others), Smith boasts a unique and finely tuned aesthetic eye that reaches its fullest expression in his All The Dead Boys project, an ongoing photo series in which the gross, gorgeous, horrific, and erotic collide using the bodies of beautiful men as the canvas. I sat down with Carter to discuss the photo series, his process, influences, and can’t-miss newsletter, Dirty Little Fridays.

What inspired All The Dead Boys?

I started in the world of fashion photography. I moved to New York when I was 17 and got a job shooting. I think I shot something for Sassy magazine when I was 17 when I first arrived and spent a long time shooting fashion, celebrities, advertising, and all that stuff. I don’t know exactly how long it was before I made my first short, Bugcrush, but it was a long time. I was already established in the photography world.

[I’ve] gradually been transitioning to film and filmmaking [full time], and that’s why I came up with All The Dead Boys. I love taking pictures: shooting celebrities, hair color boxes, advertisements, and all that stuff is great, [but] at a certain point, I looked around and I was like, “There are 35 people here hovering over the monitor, all with an opinion.” It wasn’t as joyful as taking pictures had been in the beginning when it was [just] me and my friend in high school. I would do her makeup and make her dress. We’d go to a field, I’d cover her in mud, and give her a stick. That shit. I was like, “What do I like?” I like weird fucked up horror movies and naked boys. I came up with All The Dead Boys as a creative outlet to keep me interested, engaged, and in love with making images.

When did All The Dead Boys start?

Maybe 2005 or 2006, with just a shoot here or there. It wasn’t like I stopped shooting fashion [altogether], it was something that I just wove together whenever I started to feel creatively corrupt, because films take so long. You don’t get to make them as much as you’d like. But I just kept coming back to it. For a while, it existed as a one picture a day blog. I’ve been taking pictures since then and have hundreds and hundreds of guys and thousands of images, but only started a website maybe three years ago: a proper website as a place to play with the images, and archive, and create something out of them. It’s been since then that I’ve been playing around with it more full time. I came to grips. I was like, “I’m going to be a filmmaker and I’ll shoot All The Dead Boys stuff. I’m not going to try to do the fashion stuff as much.”

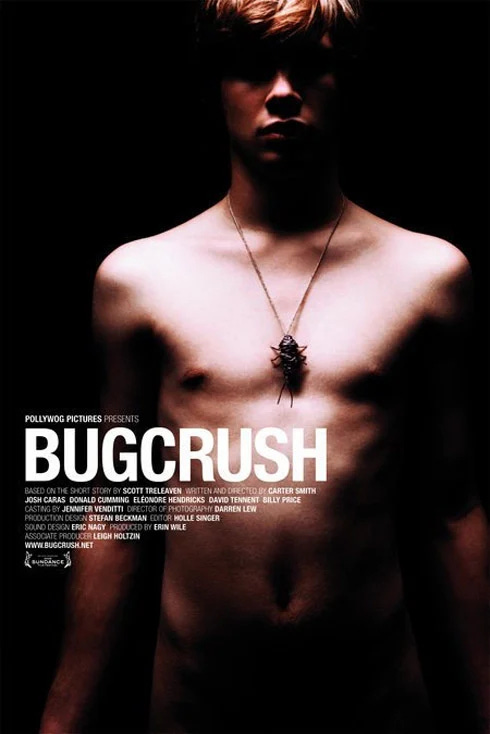

You won the Sundance shorts grand jury prize for Bugcrush, which still feels very much of a piece with what you do with All The Dead Boys even now. Would you say Bugcrush is what defined your aesthetic?

Bugcrush was probably the beginning of it. The poster for Bugcrush was probably the first All The Dead Boys shoot, in a way. That style came from me reading the short story and recognizing that it mixed all of the things that I am obsessed with; teenage crushes, cute boys in love with people they shouldn’t be, and weird body horror, all wrapped up in this perfect story.

I think the stuff you’re obsessed with follows you wherever you go. You just keep coming back to it. It’s always been there. It was probably there even earlier in fashion stuff that I was shooting. Especially men’s stories and the more editorial stuff that I had complete freedom to do whatever I wanted. There wasn’t the fake blood, and dirt, and the whatever, but it was definitely cinematic. The idea of creating characters. That’s a big part of what All The Dead Boys has always been: creating these impromptu characters when a guy shows up and figuring out a little version of a backstory that might go along with him.

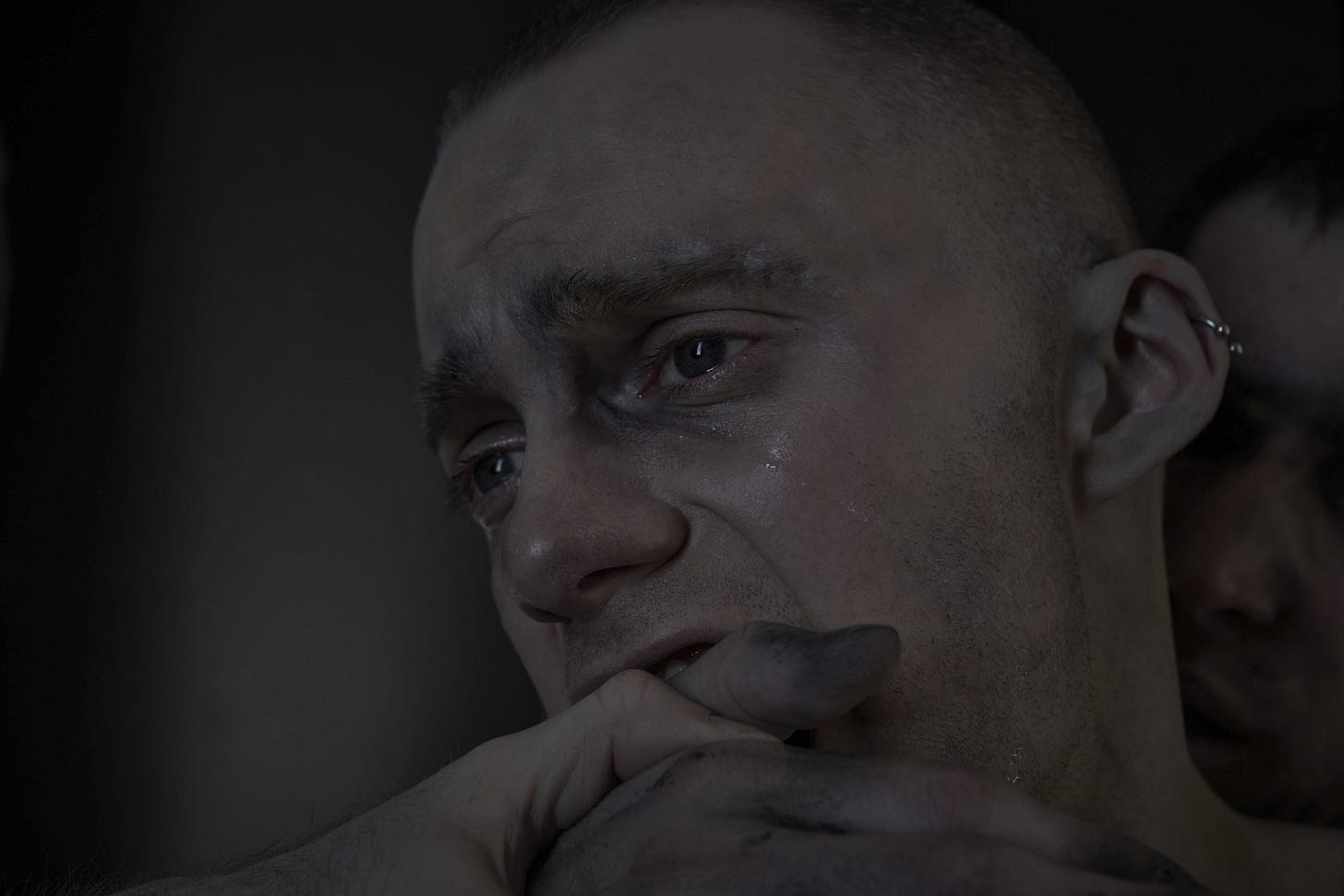

The sensual, the seductive, and the horrific. They’re interwoven in a way that has always been super fascinating for me. I think that part of what I find so exciting about [this work] is making images and stories that actually make people a little uncomfortable. That’s always been something I’ve enjoyed – that reaction of looking at something and then having the immediate reaction to look away and then wanting to look back. I think that there’s something about growing up queer in a small town where sex is dangerous, or can be dangerous. Owning that stuff is more complicated than it might be today. It’s probably one of the reasons that fear and being queer are so tightly wound.

Are there early influences that you still look to today?

I think I saw The Brood very, very young. It was the first time that I had ever felt that something was both beautiful and horrific. I didn’t even understand why I thought it was beautiful. It was the hair, and the wardrobe, and the sets – all of it was just so chic. The way it was photographed was chic. I was 12 or 11. I was way too young, I was a little faggot. I was like, “That’s stylish. I like that.” I [was also influenced by] things like Larry Clark, [his movie] Kids, early Gus Van Sant. Then a bunch of fashion photographer stuff. That is how I wound up going in that direction. The Stephen Meisels and Peter Lindberghs. That kind of world.

Cronenberg meets Larry Clark! I couldn’t put my finger on it, but there it is.

There it is! And Dennis Cooper actually. He was someone that early on, back even before Bugcrush, I was like, “I want to make a movie and I want Dennis Cooper to write the script.” I reached out. I found him and we worked on a script together. It fits perfectly with All The Dead Boys. It’s a weird, fucked up, drug addict love story with witchcraft set in the California rave scene of the early 2000s. It’s super fun. Dennis Cooper in a sort of horrifically beautiful, broken beauty kind of way is another big one.

Very similarly to Cooper, your work is about the intersection between horror and queerness. What makes them bedfellows to you?

I think the sense of otherness and the way that queer people often see themselves reflected in an outsider way. For me, being really into horror as a kid felt like that too, especially pre-internet. Like I said, there’s something [in you] growing up. I graduated high school in ‘89, moved to New York City and AIDS was not over. Sex was terrifying. The thought of sex was terrifying. That has stuck with me in a way that I think is a big reason why they’re so intertwined. It was like you sleep with someone, you die. It was as simple as that. I was convinced.

How do you find models for your shoots?

I find models everywhere. Sometimes agents, sometimes Instagram, sometimes Twitter. All different places. Sometimes, it’s a friend of someone that I’ve shot. Sometimes it’s someone who reads the newsletter. It’s random. It’s a lot of back and forth, tracking down, DM-ing, trying to figure out when people are going to be in the same place at the same time. I shot a guy last week, and we’ve been messaging for 2 years on and off. Finally, it was like, “I’m going to be in New York.” We set it up. I usually ask them to bring a couple of things. Whether it’s like an old pair of sneakers or anything else they have that’s beat up and old.

Usually, they’re a little bit familiar with the pictures, so they have some sort of an idea. I don’t even necessarily use everything that they bring, but I have them bring stuff. Then, I have bags of weird underwear and accessories. We try on a bunch of stuff. See what he looks like. What his hair is like. We start coming up with a character as he’s trying stuff on.

Then I do the makeup. I was never a makeup artist, but I thought it would be fun to learn how to do makeup. I read Fangoria as a kid. I was a monster fan. I started out doing horns, and prosthetics, and black eyes, and scrapes, and bruises. Then sometimes it looks like weird lesions and glitter rashes. There’s a bunch of different storylines that I have in my head, and I like to see what storyline this guy’s character fits into.

Do you share the storyline with him or is it something you keep to yourself?

Yeah, not specifics. “It’s an underground world of pit fighting where people fight to the death with homemade weapons. The winner gets to fuck whoever he wants in the room.” That might be our set up. “You’ve been working for 12 hours at this strip club. You took this, and this, and this. It’s 7:00 A.M. The sun is up. Blot. Go.” Like that, but nothing too specific.

Is there any gap in comfortability in creating with straight models versus queer models?

Not really. The people that show up for it are usually pretty down to play the game. Because of OnlyFans, everybody is getting naked all the time. Some of those guys, they’re just so excited to do something that’s different than physique modeling. They’re into having a character, getting dirt under their nails, getting a bloody nose, and crawling around on all fours. It’s fun for them because it’s new and different. That goes for any guy, straight or gay, I think.

What kind of cameras do you like to use?

I shoot on a little Sony A7S or A7R. I first got the A7S for All The Dead Boys because it does so well in low light. I migrated everything over to a Sony. I have a couple of lenses. It’s pretty simple because I do everything myself. I do the makeup. I do the wardrobe. I do the lighting. I do the digital capture. All of it. I try to keep it as simple as possible

Is there something you like about the look you get out of that camera specifically?

I don’t necessarily even know if it’s the look, or if it’s the form factor, the ease of use, and the familiarity of it. I don’t know. I like the fact that I can shoot in almost near complete darkness if I want to, you know? I don’t shoot as much in darkness as I used to.

How long does a shoot usually last for you?

Usually, beginning to end, four hours. Maybe five if there’s a makeup change. Twenty minutes of trying stuff on. Getting to know you. And then, usually, it gets progressively messier, dirtier, sloppier by the end. I try to save 30 minutes at the end for cleanup.

I like that you do direct them to bring something to wear, but the makeup is all you. What does that do for you as a creator that makeup is solely your purview?

I mean, it’s cool because it’s color and texture in a way that is new, and interesting, and fun. Doing someone’s makeup is intimate, because you [have to] sit there. You’re much closer to them when you’re doing their makeup than you are when you’re taking their picture. There’s this hour-long chat that sets up the dynamics of the shoot. I’m super into layers of different color, gels over watercolors, a little spray. I don’t know how to airbrush, but I really want to take a class. All that different stuff is fun. I love special effects makeup shops and spending hours in there looking at stuff, asking questions, coming up with ideas.

Speaking of intimacy, growing up gay, it’s easy to feel that certain guys are out of reach. Is there an element of this work that allows you to, not take ownership over these models, but work out those unrequited queer feelings by projecting a hot fantasy onto a beautiful canvas?

Yeah, exactly. A hot fantasy of them being super available, or unavailable, or that they’re going to beat you up, or they’re going let you in. All of them run the gamut throughout the shoot. I had one guy – a straight guy – who came in, and he’s like, “Well, just so you know, I don’t want to do any gay poses.” But, at the end, he said, “I get it now. That’s not what this is.” It’s very much about character creation and working with them or encouraging them to step outside of themselves and be someone that they’re not used to being in front of the camera. They feel like they’re not themselves and they don’t have to be themselves. It’s not, “I have to look good, and I need to be turned like this…” No, I want you picking your toenail. You know what I mean? That’s way weirder and sexier.

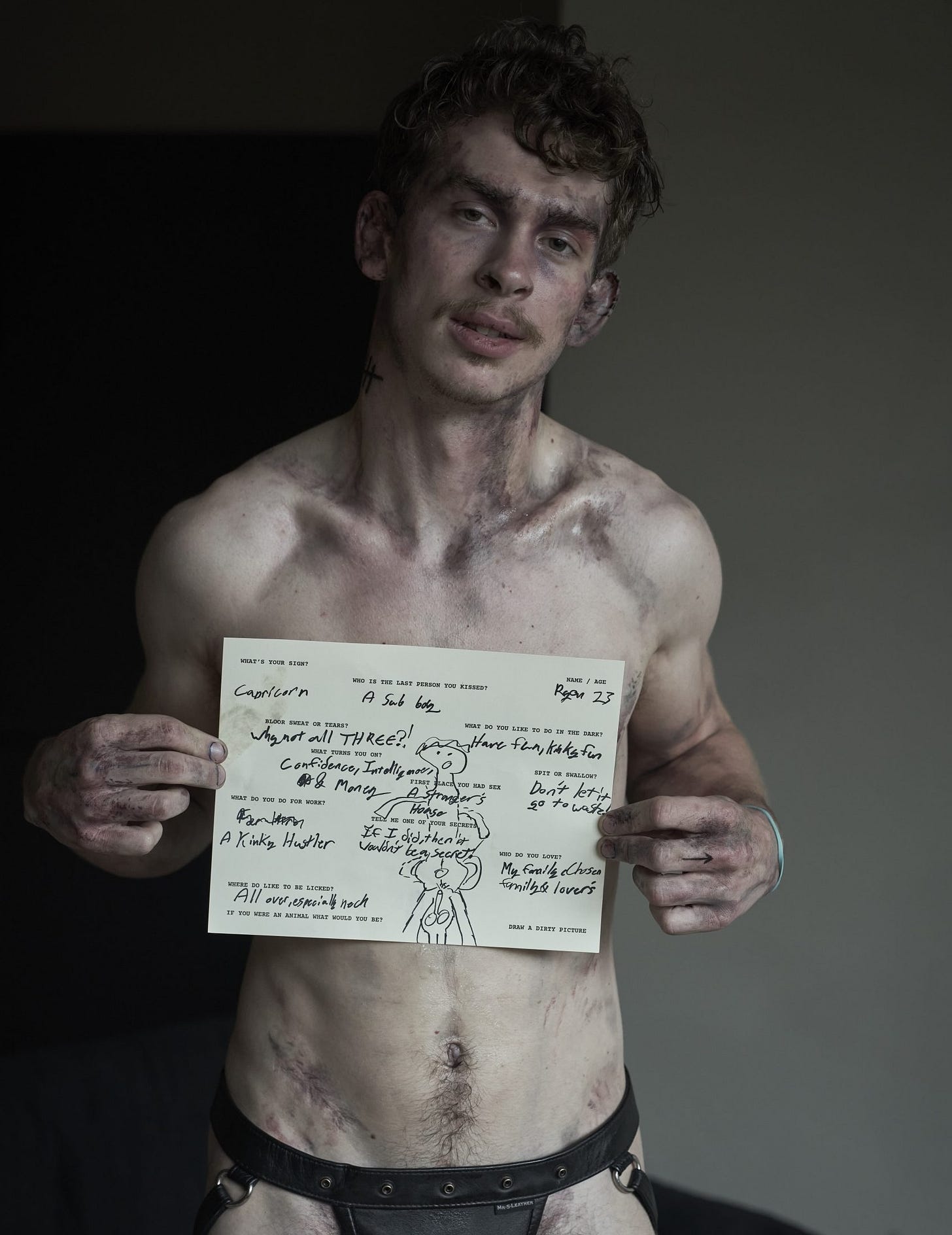

Tell me about the questionnaire you give all the guys.

I have hundreds, so I’m working on a little zine type thing with them. It started from Physique Pictorial and the symbology of what you would do for the models. I liked the idea of them contributing something other than just their image. Sometimes, I ask them to draw pictures. I always get it at the end of the shoot and I’m like, “Whoever that was that was just puking up whatever over there and covered in grease, he’s the one filling out this questionnaire. Not the guy that walked in the door. Everything on this questionnaire can be a lie if you want. It can all be true. It’s completely up to you.” Then I walk away. I let them do their thing, and it’s fun to see what they come up with.

I’m glad you’re compiling them, because they’re so cool.

I’ve got to come up with new questions though. I’m lazy about that.

They’re good questions though!

That’s true. I am fond of them.

What do you look for in a Dead Boy and how do you know somebody is right?

I look for willingness. That’s the first thing. Someone has to be down to play the game. If they’re hesitant, or not sure, or uncomfortable, that’s an immediate no. I’ve shot with guys that have just read the newsletter and been like, “I’ve never done a naked photo shoot before. I’ve never even done a photo shoot before. But there’s something about these pictures that makes me want to do it.” It’s fun to be the person that is able to do that with them. It’s a weird willingness because I can make pretty much anyone sexy for a little bit. Maybe not all the frames, but I can get the ones that I need and find something in there with just about anyone. It’s a fun thing to look for.

Do you have any personal favorite shoots that stick in your memory or any that did not work out like you hoped?

All of them have worked out. There’s always been something. I think that what’s so fun is a lot of times, I come back, and I’ll shoot the same guys over and over and over and over. There’s a guy named Ben. I’ve been shooting him for maybe two and a half years. We’ve shot maybe 15, 16, 17 times. A bunch of times. He’s always the same character. He’s always Ben. It’s Ben in Joshua Tree. Ben in New York. Ben in Los Angeles. Ben in Austin. And he has this storyline that we keep coming back to. He slips right into being Ben. Ben is very much based on him and who he is. It has evolved.

Ricky is another character who I love shooting. Oftentimes, what happens is, I’ll go and write something for these characters. I wrote a series that Ricky and Ben are at the center of. It’s a middle-of-the-desert strip club called Suckers. That was written because I love Ricky. I love Ben. I love Asher. I love Chan. I wrote for these guys with them in mind. And then Swallowed. I met Jose who plays Dom shooting him for All The Dead Boys. That was the beginning of that movie, which is crazy.

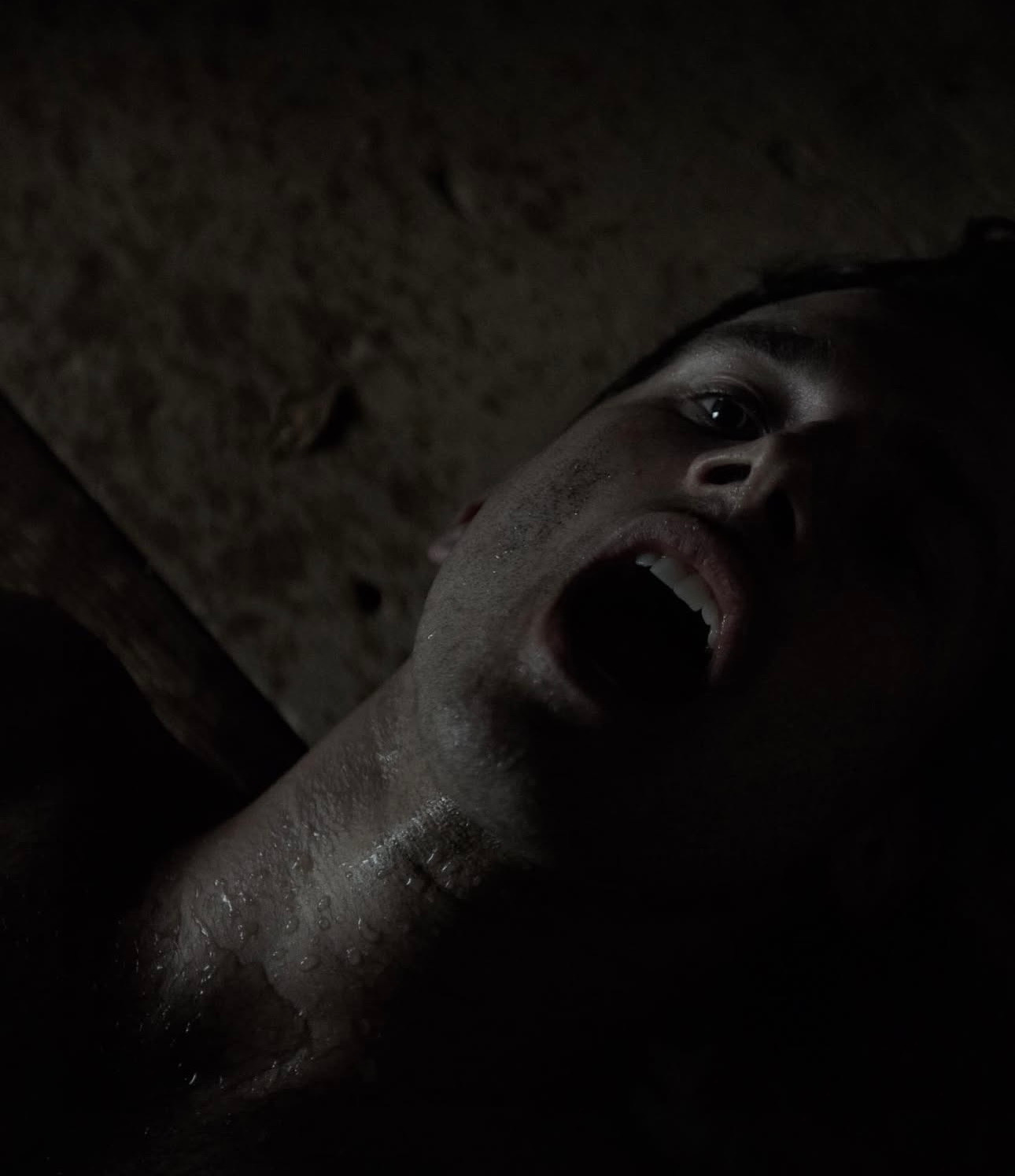

How would you describe your own aesthetic?

I’m always looking for that spot where the beautiful and the horrific overlap. They’re smutty, and they’re slutty, and they’re sleazy, and sweaty but they’re also beautiful, and sensual, and delicate in a way. It’s the contrast for me between hard and soft and scary and sexy.

I remember you said once in your newsletter that the boys are “sweaty and ready for whatever dark and disturbing shit is headed their way.”

Sweaty and ready is a good way to put it!

One could say that the implied violence in your work – eroticizing the threat of violence that queer viewers face every day – could be seen as problematic. That’s not my personal view, but how would you address that?

I think that the violence that’s implied is never specific. Everyone takes away something different from looking at the images. You’re never told this person is queer and was beaten up or this person is going to beat you up if you’re queer. More than anything to me, it’s an aesthetic more than a…

A message?

Message. Exactly. I’m more looking to talk about messages and representation when I’m telling a long form story or writing a script. The images are all about the aesthetic, which is so specific. It’s strange because the people that respond to it really love it. It’s not a 60% like: people are either in or they’re out. It’s all people that really want to go on the journey with me.

It is interesting because your images serve a similar purpose to kink where traumas can be worked out in a sexual play space, both for your viewers and you as a creative.

Yeah, there’s an STD sort of ribbon running throughout, a thread that binds a lot of this imagery together. I think, again, that’s from growing up in that time and feeling like sex is dangerous or has the potential to be dangerous.

Tell me a bit about your weekly newsletter, Dirty Little Fridays.

I was getting ready to start shooting Swallowed. Or maybe I had just finished. I was like, “I’m going to have this movie. I don’t have a mailing list. I don’t have a list of people that are going to open emails for me that I’m going to be able to talk to this movie about. I better fucking start talking to these people that are going to be my audience here.” I decided to commit to putting out a newsletter every single Friday and trying to get the like-minded people that are into the same shit that I am on board.

It’s been a fun experiment and it’s become one of my favorite things. One of my favorite creative outlets, even. I never know if anyone’s actually reading it or if people are just there for the hot pictures. I think it’s half and half.

You must get a good enough response to keep going, though.

It’s been great. I don’t do any real heavy pushes to grow the list, really. The people that find it love it and they share it with other people that love it. It creeps along, getting bigger and stronger. I’m really happy with the open rate and the engagement. That’s exciting. If you’re just sending something and you realize how few people are paying any attention, it can be pretty disheartening. It was like that for a very long time.

When people take the time to write, to respond, I get the most heartfelt, touching emails from people that are just so happy to have access to see something that makes them feel like these pictures make them feel. I think it makes a lot of people feel seen and understood in a way that I don’t even comprehend as the person making the images. They connect with them in a way that makes them feel less alone, weird, crazy, freakish. That is so fucking cool.

You’re wearing your freak flag right in front of everyone by sharing these photos and making it okay for others to do the same. It does make people feel less alone and free to admit to being turned on by things that maybe we shouldn’t, right?

Not even that we should or shouldn’t, but something that doesn’t look like what the poster in Target says gay people are supposed to look like.

What are you working on currently?

I did a short film called Sucker. It’s on the website. It was a proof of concept, done really small. I then wrote a longer piece called Suckers, where the boys have a little something extra to offer. The sad part is, it’s something like Swallowed or a lot of the other All The Dead Boys projects, meaning it’s something that scares 99.9% of people off when it comes to actually getting it made. It’s not in limbo, but it’s not like I’m in production. I’m in prep. It’s very much running through the background. I wrote it with Joe Lipsett, who is amazing. We had so much fun.

It’s one of the worlds that it has been created out of All The Dead Boys. It’s from shooting Boys and moving into this weird go-go, punk rock, glam, glitter bomb, morning after, street hoe look. That’s how the aesthetic of Suckers was born.

Last year I did my first All The Dead Boys pornzine called 52 Fridays with lots of the graphic, slutty, sloppy stuff. A sort of raunchy “best of” to celebrate a year of sending my newsletter. I loved the process, and, of course, the end result so much that 2026 is gonna be a year of more pornzines. I’m kind of obsessed with the idea that these images only live in a tangible, tactile place. Not on Patreon, which still has a certain amount of censorship, or Instagram, or any other place, [but] in little zines where the ink can rub off the more you touch them. No fancy art books – think grubby ‘80s porn mags!

I’ll be doing a whole series of Backwoods Boys zines, mostly shot on location in Maine playing with the whole rough around the edges, might-wanna-fuck-you-might-wanna-kill-you aesthetic.

[But the] biggest thing I want is for people to subscribe to Dirty Little Fridays. It’s sort of become a creative lifeline for me. In a time when getting films funded and made can take so long, the weekly schedule of releasing a newsletter is both terrifying and oh so gratifying. It’s been amazing.

You also recently had a big, high profile shoot with Tom Holland for Men’s Health. Did I detect a bit of the All The Dead Boys influence?

Yeah you definitely saw some ATDB in the Tom Holland shoot. I wasn’t doing the makeup like I normally do, but you better believe i was on top of his groomer making sure the sweat, dirt and grease felt authentic and sexy as fuck.

What do you hope fans take away from All The Dead Boys and Dirty Little Fridays?

I hope that they take away that there might be other people that like the same stuff they do. They don’t have to keep it in the dark and pretend they’re not fascinated, and repulsed, and seduced all at the same time by it.

And to wrap, I want to pose two questions you ask yourself on the All the Dead Boys website: What scares you? What turns you on?

I started being afraid of the body when I was a teenager. Now that I’m aging, I’m afraid of the body again in a completely different way: weird things breaking down or not working. It’s this idea that you’re forced to confront some of the stuff that is out of your control. It’s the human condition.

What turns me on is also what scares me. It’s the same thing.

Visit allthedeadboys.com to subscribe to Dirty Little Fridays and keep up with Carter.