In the Dark (2000)

A Conversation with Clifton Holmes

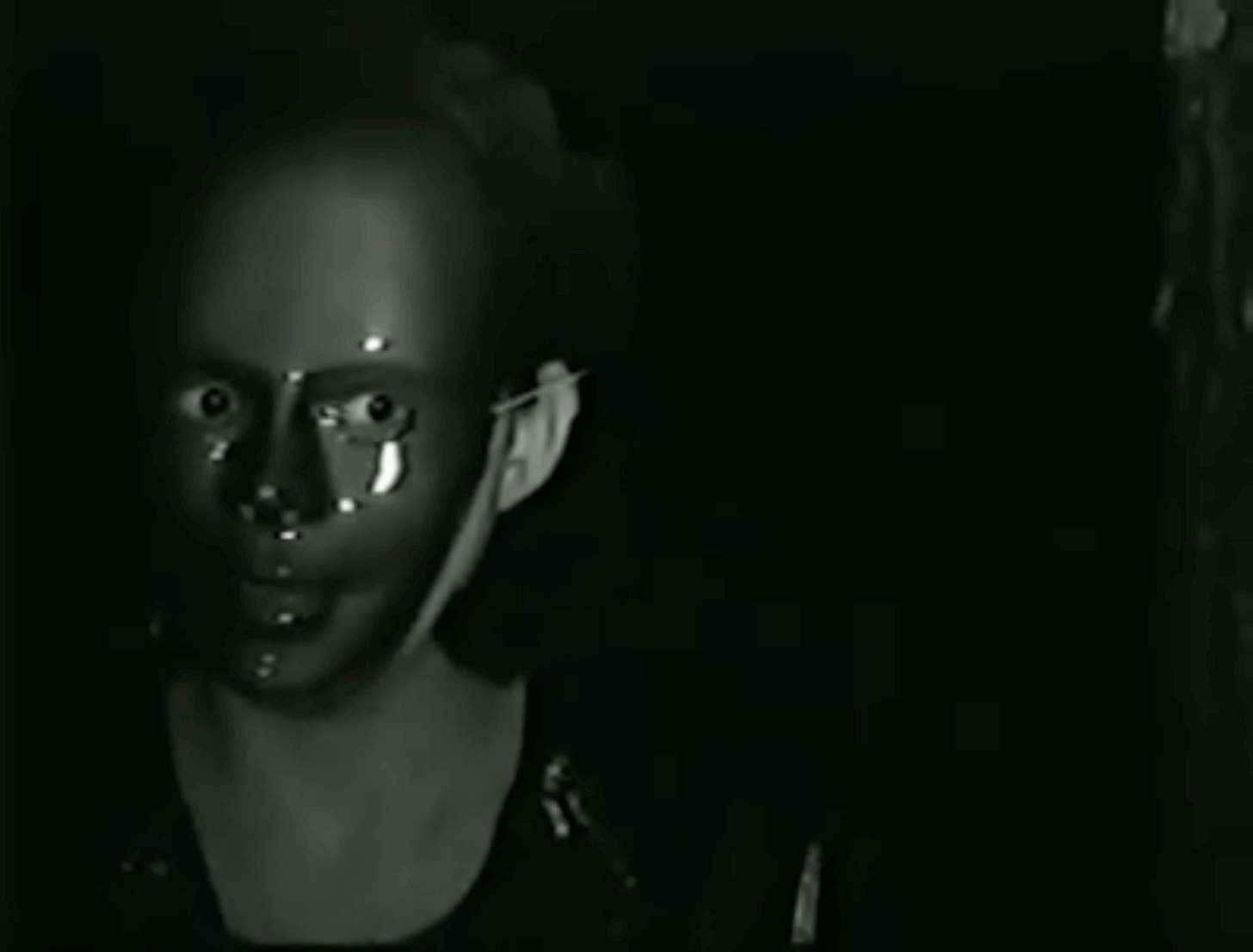

I first found out about In the Dark last year and haven’t stopped thinking about it since. I don’t recall whether I first encountered a heavily pixelated screenshot in a social media thread or caught the title via one of the countless random user exchanges I peruse on Letterboxd, but once I learned of Clifton Holmes’ virtually unseen shot-on-digital masterpiece, I was bewitched. Based on a novel by Splatterpunk writer Richard Laymon about a young librarian named Jane who finds herself drawn into a game of danger and financial rewards by the mysterious MOG (aka Master of Games), In the Dark was never meant to be seen, and has been kept alive thanks to a small group of cinephiles with a taste for the lo-fi terrors of films shot on early digital video.

The experience of watching it one lazy Friday on a grubby YouTube rip in the dead of night immediately possessed me with a need to know everything (anything!) about it. Luckily, its creator was easy to find and even easier to chat with. Though to speak with the filmmaker risked demystifying a bizarre film that feels like a ghost transmission from a nightmare reality all its own, getting to know Holmes merely solidified my love for In the Dark in all its rare, rough-hewn beauty – a creation that refused to disappear into the netherspace of lose media and deferred ambitions, even against the wishes of the man who made it. Read on for our conversation.

Just to start off, tell me about your background. What led you to making this movie?

I was a fan of Richard Laymon. I know a lot of people take exception to some of his material, that he’s a splatter punk writer or whatever, but I liked it. My friend introduced me to his books, and I went through a bunch of them. I was like, “It’s such clean prose, it’s almost like watching a movie. Has there ever been a movie made of this stuff?” Nobody ever had. I was a film student at Columbia, and I was like, “Well, I’ll just reach out to him.” So, I did, he got back to me, and basically [said] “Yeah, that’s a cool idea. Why don’t you go do it?”

I was young, I wanted to do something [so] I adapted the script for one of his books, probably whatever was the most recent one. He really liked it, and I thought it would [require] too big of a budget, but I contacted a number of production companies out in L.A. Turns out, filmmakers had tried to make movies based on his novels before: Richard Donner (Lethal Weapon) optioned at least one of Laymon’s books, but they could never get it done. It always got up to the money point, and then people would be like, “This is too much. It’s too violent, too psychosexual, too juvenile. People are going to protest.” So it just would never get made. I started having that exact same experience where I went from one production company to another company to another company, and they’d always say the same. Or, we go through some development, and then they’d be like, “Oh, well, this is a heinous killer. Could we [make him] Middle Eastern ?” I’ll never forget that. They said, “Nobody’s going to believe a white guy would be killing this many people.” I’m like, based on what?

This is before 9/11, but still, there was this mindset. I’d go to Richard and he’d just say, “Hell no. What are you talking about? That’s not the story.” The thing is, he was a writer and he was making his living writing – he wanted movies made of his books, but he didn’t need the Hollywood money. So he’d just keep turning it down, and I really respected him for that.

[Finally], I was like, you know, fuck it. I like independent stuff – I’m going to identify a book that I could do for a super low budget. I don’t know if this is true or not, but I had heard that for A League of Their Own, what Penny Marshall did was she took a whole bunch of Barbies and a video camera, and pretended to do the movie to show that it could be a good movie, even with a bunch of Barbies. So, [in essence] I wanted to do that same: I’m going to make a movie, super low budget, just to show that you can make a Laymon movie that is not going to be overly graphic, not too violent, and people aren’t going to, like, start tearing up a movie theater because they’re pissed off or whatever. So that’s how it all happened.

So the In the Dark that we have is more of a proof of concept than anything?

That’s exactly what it is. It was never meant to be seen. It was meant to be seen by producers, just to go, “See? You can do this. Now let’s do this for [real.]” But even with the small budget that I had, it wasn’t finished. I didn’t have the budget to add the right sound effects: I wanted maybe $1,000 for finishing funds so I could smooth out the audio a little bit. No matter how rough and cheap this movie looked, I wanted good sound. Some [funders] offered to help so I gave them a copy, and they said “[We think] this is done. You know what, we’re starting a film festival. Why don’t you let us screen it?” So that’s what got the ball rolling.

And that was the Chicago Underground Film Festival?

Yeah, it played the Chicago Underground Film Festival, San Francisco, and then it played the Independent Film Market in New York. And then it’s just played here and there [over the years]. If people do a request to screen it, I’ll be like, “Okay, all right,” and ask the Laymon estate.

Are you proud of it as it is? I know it’s a proof of concept and you seem a little uncertain about it, but what do you think of the material you have that’s gaining a bit of cult status?

I’ll you what, you like it, so that is fantastic! I’m so happy. The thing is, this movie was brutal to make. I’m a very meticulous person. I will storyboard out everything, [but] I don’t think that there is one scene in this entire movie that fit my storyboard. Everything would fall apart at the very last minute. One of the scenes, we had an actor who just didn’t show up, but we had the location. So the actress who’s playing the lead, she called a friend who had just got done shooting a commercial or whatever. The friend came running over, read the dialogue, and then we shot it. That was what shooting the movie was like constantly. So now every time I watch the movie, I start getting flop sweat.

When it played the Chicago Underground Film Festival, we got a really good review in The Tribune, so there were a lot of people that showed up: there were people actually sitting in the aisles, and I was freaking out. I couldn’t even watch the movie, I was just in the bathroom just pacing back and forth with the whole thing going, “Oh my God. This is terrible. This is the end.” But because people [have seen it over the years] and like it, they’re seeing stuff that hopefully matched my intention, right?

I totally understand your reaction. But just so you know, I think it’s a masterpiece. Everyone I’ve shown it to who has similar taste is like, “This is incredible. Where did this come from?” A new generation of film fans, we’re really high on this movie and think it’s really amazing, even just as a proof of concept. Doubling back a bit, did Laymon write on it at all or was this version of In the Dark all your hand?

No, it was just me. He was busy writing his books. So, I’d send him a script, he’d say, “This is going to be great,” the studios would have their problems, and then it’d be on to the next one. Did you say you read the book?

That was going to be my next question: I think your ending is far superior to what the book does. I know you obviously needed to make it simpler than what’s in the novel, but it’s so different in tone, so different in every regard. So, where did that come from?

I [chose In the Dark] because that I thought it would make a really good, small budget genre movie. But, one of the things that I was actually looking forward to was that ending but I didn’t know how I was going to conceive the shoothout, the monster that is the Master of Games. Well, of course I couldn’t do it. Under my budget? Forget it. So, I ended it a totally different way where there’s still a confrontation but Jane dies or something. I was okay with it, Richard was okay with it.

When it first screened, the movie gets over with, and everybody’s walking out of the theater all quiet. It was like a funeral service, their heads are down, and I’m like, “Oh my God. It’s even worse than I thought.” A friend came up to me, and I was just like, “Oh my God. Was it that bad?” And they said, “No. It’s fantastic. [Everyone’s] just re-evaluating their lives.”

It turned out to that people liked it, but they were leaving kind of down. I didn’t like that, it kind of hit me wrong. I thought, since I couldn’t do the book ending, instead of just cutting it off and having a dark ending, how can I make this a little bit more interesting like add something to it? Let’s just take this further. What happens if she keeps doing the game? Where is this going to end? She started bored, but if you have this game which you keep playing, but you keep winning and you get so much money that you could do whatever you want, but you’re still forced to keep playing the game, how’s that any different than a job that you don’t want to do and you’re still stuck, right? So, I wrote that ending. It’s funny that you say you like it better than the book because, I showed Richard what I’d written for the new ending, and he says “Cliff, I wish I would have thought of that ending.” Unfortunately, the died before I was able to shoot it. So he never saw the end.

That’s a shame. How long after the initial shoot did you shoot the new ending?

Probably a year. It’s hard to say because the actual shooting of the movie itself took probably two years. I was working a job, everybody was working a job. I’d go to the Chicago Film Office, I’d look up locations. I was doing the scouting, everything. I’d get all the props for the scene, all of that. It was just like one weekend here, one weekend there. Eventually it got done.

What were you shooting on?

MiniDV. It’s still in my closet. To this day, I kind of regret having not shot on film just because I love the look of film. But at the time…you’ve heard of the Dogme 95 cinema movement, right?

Oh yeah, big fan!

We had heard that somebody was shooting a movie on digital with no extra lighting and stuff, The Celebration, and it was going to be playing over at the Music Box. So, me and my brother, who was financing the movie, we wanted to see how it looked projected on the big screen, and if that worked, we were going to shoot video because that was going to be so much cheaper. And it looked good! So, we went with that.

I love the MiniDV aesthetic. As a millennial, I grew up watching Lars von Trier, Vinterberg, and like horror shot on early digital as well. I think at the time, as a kid, I wasn’t that into it, but looking back on it, it really is its own unique flavor and style. I know you regret not shooting on film, but I think the digital aesthetic is definitely a piece of what works about the film and makes it unique.

I don’t want to credit my genius or anything, but it was funny, we started shooting, and then we heard, “Oh, somebody over in Maryland is doing a video horror movie…”

I think I was still in the middle of editing when The Blair Witch Project came out. Sometimes it was annoying, because our film would always be compared to Blair Witch, just because of the proximity. But I’ll take it.

In the Dark is more formalist and classical in structure, so they really couldn’t be more different. You talked about how you work from storyboards…I think what is so compelling and unsettling is how tight and controlled everything is despite the rough edges. I know you said it the sound is unfinished, but I love how spare everything is with the repetitive drum stings…

I wanted it to be drum stings.

Are they not drum stings? What are they?

If I had money, it would have been a drum sting. I didn’t have access to a drum. Only one person has ever actually accurate figured out what it is. It’s a basketball.

You’re kidding me.

No, no. Because I didn’t have a drum, I thought I’d replace it eventually, but that never happened. Only one person has ever guessed what the stings are. They came up and asked,“Why’d you use a basketball?” I was like, “How’d you know what it is? Damn it!

So tell me a bit about your lead, Kim Garrett. How did you know her? Did she just answer an open call or something like that?

She just answered an open call. We looked at a number of actresses. I was wanting someone from the Chicago theater scene, and I saw her and I was just like, “I like what she’s doing there.” She seemed very game to do this.

How was the working relationship?

The working relationship was tough just because she was young and she was more a theater person: she was used to doing a couple of performances a day and then it’s done, right? Film is one scene here, one scene there, months later. She was not ready for that, she wanted it done. We were all new to this, but It got harder and harder as time went on and we weren’t reaching the finish line. She was great, but she just wasn’t prepared for the timeline.

The marathon of it.

Right. And it was little things, for example: that’s not her real hair. I wanted that Louise Brooks look. We hunted around Chicago for a wig and then cut it to that shape. She was in charge of that wig, damn it. She was the wig wrangler, and she had just thrown it in the back of her car. Sitting in the back window with the sun, it turned into like a resin helmet. It became like a football helmet, just a solid thing. I’m like, “How in the hell am I going to shoot this thing?” She was like, “Man, sorry about the wig.” I was like, “God, Jesus.” She was younger and she wanted to party. This [shooting schedule] would be an infringement on anybody, so I don’t blame her, but it was a lesson learned anyway to just be aware of where people are coming from when they’re going into a project.

But it was funny, because it was such a slog, especially toward the end, but she’d still do the scene. She still really liked the product, she just hated having to be there to actually physically go through the motions of it. We got to the last scene, and then she’s like, “Oh my God. I can’t believe this is done and we’re not going to see each other again. If only we could keep doing this.” It was like, where was this person months ago?

Do you know what happened to her? I know she had a couple additional credits, but not much. Just a couple of things listed on IMDb.

It’s been a while since I checked her out on IMDb. She’s a very spiritual person. I know she went off to India actually to work with children.

Kind of the direct opposite of where she ends up in this movie.

Yeah, she’s paying it back. But that was so Kim though!

I also wanted to talk about the central house of horrors sequence. There is a song in that scene, the only music in the movie…

I love that song. If you’ve ever seen the movie Head, it’s a song written by Harry Nielsen, performed by the Monkees, and Davey Jones does the singing. I would say an homage was what I did. I can’t remember what happened [in that scene] in the book. It’s like, they’re watching something. it was some movie, I think with Barbara Streisand…

I think it was Funny Girl, maybe.

Funny Girl! I wasn’t going to get the rights to that. Funny Girl would have been interesting, but I kind of like the idea of starting fucking with the audience, where [as a viewer] you’re going along, and you don’t know what’s going to be around the next corner.

I love that. It still matches the tonal shift of the house in the book and the film because everything up till then is sort of banal, but then it gets really insane really quick.

Yeah, it’s a horror place and you’re going to see horrifying stuff in there, but you’re right: I was trying to capture what was in the book kind of like when I was first reading and I didn’t know what to expect, and the chick’s eating her arm and stuff like that. You may be expecting some horrible thing around the corner, but you’re not expecting this. This kind of weirdness.

Speaking of fucking with the audience, your movie also switches to color for a single, very jarring moment. Can you tell me a bit about that?

In the book, what’s happening to her isn’t really clear, right? She starts getting messages in her sleep from The Master of Games or some other player that MOG is telling to mess with her. I had thought that if I was Jane, I’d do something to to to catch what’s going on, right? So, she sets up a camera to catch what might be going on. But, I thought, “Nowadays, video is in color, so it wouldn’t make sense to have a black and white video for that.” [I’m showing] the audience what’s on her camera, so it’s color. To me, it’s like arty-farty kind of, oh, now you’re seeing what’s really going on.

Are you a Silent Hill fan or was that somebody on the crew’s suggestion?

I like Silent Hill! I did get the rights to that! I wrote somebody and they gave me this form. I was a Silent Hill fan, but one of the funny things that always struck me is just how much time is spent in that game just running around. I wanted to [use it to] show that she’s bored. Anytime she’s playing, I just wanted to use the boring parts instead of anything scary happening. Arty stuff, again.

Obviously this film was a proof of concept, but did anything ever come of it? Did you have conversations with anyone or did this just disappear into the ether?

There was a player in the film video market, this is way back in early 2000. They made some hits and stuff. Somehow, somebody had gotten a copy of the movie and they showed it to somebody’s assistant. That assistant sent it to the head of the company, who happened to be in Cannes at the time. Suddenly he’s calling me, and he’s just like, “I just saw your movie. We’ve got to have a meet!” So I went out to LA, I met with him. He said, “I got a VCR and I watched it late at night. That was the best experience I had all Cannes! We’ve got to do this movie.” Then you fast forward weeks or so, and then it’s just like, “You know, I don’t know. People might be spooked out by this movie.”

That’s the point!

It got really good reviews in The Tribune, it got good reviews out of San Francisco, and the person who recommended my film him was a female. There’s a lot of women who really like Laymon, they like this movie, but always there’s this, I don’t know if it’s a weird patriarchal thing or something where it’s like, “We’ve got to protect the women.” He said, “The women are going to be offended.”

So it was just the same old thing: the [window of opportunity] slowly goes away. Then, we had some interest from a big film company, but it was the same thing. Unfortunately, it kind of came in at the wrong time. Scream had some out, so it was all the ironic stuff, it couldn’t be something serious until Blair Witch. But when Blair Witch came, it wasn’t gory or anything, it wasn’t like my film.

It was the typical Hollywood thing, just no more calls, no more calls, no more calls, and they won’t even return your calls. So, yeah, it just died. And then there was that whole French splatter or torture porn thing.

Yeah, New French Extremity.

Yeah, Martyrs, High Tension, Trouble Every Day. I’m like looking at those, and I’m like, “Wait a minute. Those things are way more extreme!” And then coming from Japan, you know, with Takashi Miike’s Audition and all these extreme bloody thing. [My film] wasn’t going to come close to that level of violence.

Have you had people reach out to you about restoring it and getting it out there on physical media?

Over the years, there have been people who have approached me. Some things irk me, where it’s on YouTube and it’s on Letterbox. I literally have no idea how they got these. No idea. Nobody’s ever contacted me. People were selling it online. It’s like, the people who contact me end up not doing anything with it, and then other people just grab it. Money, especially now, that doesn’t matter, but, it’s a lack of respect or something. Why don’t you just ask me?

In one sense, from the artist who made it, it’s kind of annoying, but from another sense, the deeper creative parts, people like you are out there and they’re watching it and they’re liking it, so that’s great. I’ve been working ever since then, so it’s weird that something that I worked on way, way, back when I was another person is still getting attention. But it’s satisfying, right?

It’s just strange because it’s the sort of thing where the mystique of it adds to its allure. And then suddenly it’s like, where is this guy? Where are all these people? What is this? It’s like, you just want to know. Movies can have a weird, long life that’s kind of you don’t expect, I think.

By talking to me, does it ground it for you so it’s not as interesting?

No, no, no. It’s still deeply interesting.

I’m curious.

It’s still extremely interesting. I’d still love In the Dark whether we spoke about it or not. I’ve been spreading the gospel about it and I will continue to do so. I know you did a feature, Pagan Holidays in 2014. Do you have any desire to pick up another digital camera and make another movie again?

Oh, absolutely, one thousand percent. Ever since I made In the Dark, I’ve been trying to make movies. And then ever since, the one I will not name, Pagan Holidays.

Sorry I spoke it!

It’s been hard to get a budget. I have so many scripts, it’s crazy. I’d still like to make another movie, but I’ve been busy writing a book series. Writing books is so much more satisfying because I don’t have to worry about locations. I don’t have to worry about actors. As long as I’ve got a place to write, I can set the scene up just how I want it.

Tell me a little bit about your book series!

It’s a series of five books, called the Amalina Dalca series. I’m the worst salesman of my stuff. I ramble, right? But not in my books. Anyway, people in the reviews, they’ve called it “dark fantasy,” so I guess it’s a dark fantasy series. It’s about this girl who gets swept up into the clutches of this evil entity that, let’s say he’s a vampire. He’s not a vampire, but he might as well be a vampire. She should have been one of his victims, but she wasn’t and now she got pulled into his service.

It sounds a bit like In the Dark! I do want to ask, Cliff, why do you think people like me are taken with your movie despite the flaws you see onscreen and the way it’s been so under-the-radar?

I don’t know, I was going to ask you why. Not that you’re wrong to like it. Anybody who’s liking it is recognizing something genuine. It was made by somebody who genuinely wanted to make a good movie, that was working on the craft of it and was trying to use techniques that he hadn’t seen before. Now I’ve seen these techniques done a bunch of times, but at the time, I hadn’t, and I was trying things out. You’re watching someone who’s genuinely just trying to do something with an audience, trying to capture the Laymon experience. Because it’s genuine, I think people maybe are responding to that. Maybe it worked. It works. I’m glad.

Is there anything thematically that you think has aged well about it?

I have no idea what Richard was creating in his book, but the political dimensions for sure. I could not have predicted the passing of that whole economic atrocity of a bill that the Republicans cooked up last year, but I felt it coming from decades ago, from the Reagan era, and in the ‘90s with the corporate democrat continuation of the hatcheting away of the middle class and economic viability. I grew up in a divorced family setting, being dragged from one place to the next, living one year in an attic, another in well-to-do multistory houses, others in the cheapest of apartments, almost never the same school twice from year-to-year. I had a first-hand survey of living poor, middle-class, and even lower upperclass. I saw how fickle money was, and the lifestyles of the poor and rich alike. And from the 80s on, I saw how the wealthy, wearing the republican party like a cheap suit, were on a quest to send this country back to the gilded age, and the vast majority of people would be pawns.

For me, the story of In the Dark became analogous to the empty pursuit of individual wealth, and how the truly elite can just play with the little people like toys, for their own amusement, using money as the carrots-on-sticks and cheese rewards on their traps, while those littles, no matter how much money they seem to gain, remain safely locked inside the boxes their masters have constructed for them. It also is a critique of the individual playing into the paradigm, instead of focusing on personal growth, relying on outside forces to guide your life.

That kind of stuff gets veiled over because this is supposed to be strictly entertainment for everyone, but that was all there.

Keep up with Clifton and the Amalina Dalca series at https://clholmesauthor.com/.